. As I watch him do truly impressive lunges and blocks with the Okinawa-style fighting stick called a bo, my muscles tense in ways that mirror his movement even if I'm sitting in a chair at the time. This kind of thing happens fairly commonly: you watch a baseball game on TV and so feel like shagging balls with your kid, or you imagine throwing a discus and then do it exactly the way you imagined it. The link between physical activity as it is seen in the real world (witnessed) or in the mind's eye (imagination) has been established by researchers in everything from neurophysiology to sports psychology. But as I twitched and flinched while watching Shihan Nishiuchi last month, my mind turned to a research study I'd just read about in the journal Science

. As I watch him do truly impressive lunges and blocks with the Okinawa-style fighting stick called a bo, my muscles tense in ways that mirror his movement even if I'm sitting in a chair at the time. This kind of thing happens fairly commonly: you watch a baseball game on TV and so feel like shagging balls with your kid, or you imagine throwing a discus and then do it exactly the way you imagined it. The link between physical activity as it is seen in the real world (witnessed) or in the mind's eye (imagination) has been established by researchers in everything from neurophysiology to sports psychology. But as I twitched and flinched while watching Shihan Nishiuchi last month, my mind turned to a research study I'd just read about in the journal Science .

.Three scientists from Utrecht University in the Netherlands reported in "Preparing and Motivating Behavior Outside of Awareness" that they were able to demonstrate the presence of subliminal influence of even just the idea of physical activity on the speed and force of muscles. Notice both the words I italicized.

• It isn't just that someone watched a basketball game and it made them go play basketball, too. In that case, they would at least know that they'd seen people playing ball and it had made them think maybe they'd like to as well. But in this case, someone's body -- in fact, the bodies of 42 test subject someones -- responded to a cue of which they were not consciously aware. It was as if they went to a noisy bar where a basketball game was being played on a television that was not visible from their bar stool and not audible in the hum of conversation and clanking glassware -- and then, without realizing they'd heard a basketball game, decided, "Hey, I think I'll go shoot some hoops."

• More amazing, in this case it's as if what was on the bar's TV wasn't even a game, but merely a couple of commentators talking about jump shots and free throws, so that only the idea or concept of basketball, as words, was floating around in the person's subconscious to stimulate the going-out-and-playing of basketball.

OK, so now imagine that scenario: two game commentators are talking about basketball on a TV in a bar where you are sitting, and the TV is outside your vision and you can't consciously hear because of the noise in the bar. Could that situation really make you want to go play basketball? And if it did might it make you play better than you usually do? The research these guys at Utrecht did strongly suggest the answers are yes, and -- surprisingly -- yes.

Here's what they did in their study. They plopped someone down in front of a computer screen, gave him or her a gripper that measures how hard you squeeze it, and told them to squeeze it as hard as they could when they saw the word "squeeze" appear on their screen, then let go when the word vanished. And then they recorded what happened: Squish, release, wait. Squish, release, wait.

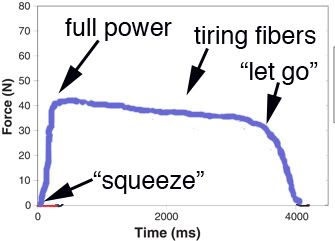

It takes a moment for a person's body to respond when you decide to move; there's a tiny lag time that can be important if you're trying to catch a cup that's slipping out of your fingers, for instance. Then, once your body responds, it can respond in an all-holds-barred kind of way, a lackadaisical "oh what the heck" kind of way, or any sort of way in between. Someone in the Dutch study with great reflexes and really strong hand and forearm muscles would have a shorter lag time after seeing the word "squeeze" and they would probably squish the daylights out of the gripper handle. So if you looked at a plot of their response (hypothetical in this case, just to show you how it works), it would be something like this:

The blue line shows you the reading on the squeeze-measuring thing after the word "squeeze" shows up on the screen in front of Mr. or Ms. Atlas (I was going to write "Mr. or Ms. Universe" because Mr. Universe is a bodybuilder type who would probably pride himself on being able to bust the gripper thingie in under a microsecond flat. But then I realized Ms. Universe (is there a "Ms." U?) is, well, something entirely different. Which is food for thought of a whole different nature…). At 0 (zero) seconds of time, when the experiment begins, s/he's not squeezing the gripper yet and the word's not on the screen yet. That's the point in the lower left corner of the graph where everything is zero (0). As time begins to tick past and the word "squeeze" shows up, M/M Atlas squishes the gripper, which automatically measures how hard s/he squeezes it and therefore how strongly or fully his/her muscle fibers are responding to the command to "squeeze." So in very short order, the gripper registers that about 40 Newtons of force are being exerted by those muscles. (A Newton is the amount of force required to grab a little matchbox car weighing about half a pound -- ok, so not such a little matchbox car at that -- and shove it hard enough that it accelerates at about 3 feet per second per second. Go shove a big apple across the floor and you'll get the general idea. Two extra points if you can figure out why they named this unit a "Newton". And if your mind wandered automatically to cookies during this paragraph, we are no doubt related.)

So where was I? Oh yes, the graph. You will see on the graph that after the initial burst of power, the strength of the person's grip actually goes down a little, but steadily. That's not intentional, but just has to do with the way muscle fibers work. Anyway, then at the end the word "squeeze" goes off the screen and -- again with a bit of lag time, during which period the person's muscles start relaxing (as you can see by the precipitous drop in force) -- the person lets go and the force reading on the grip drops to zero again.

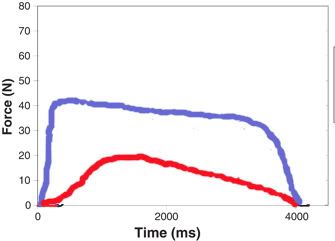

Now consider, just so you can see how phenomenal the results are that I'm going to share with you in a moment, what this grip might look like for someone who really doesn't care much about the experiment and furthermore wants to go have lunch instead of squeeze a little gripper thingie in a laboratory. That person's graph of hand-force is in red on this chart (where the blue one is that of M/M Atlas from before, so you can compare them):

Notice it took longer for Mr./Ms. I'd-Really-Rather-Be-Eating-Lunch to notice the screen says "Squeeze" and to care enough to respond. And he/she doesn't give it much of a go, so the amount of force they exert is never as high as it is for M/M Atlas (who is trying to break the machine so s/he has boasting privileges in the gym).

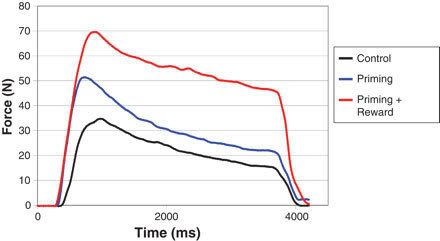

Now I can show you what Drs. Aarts, Custers, and Marien did. Their 42 testees were paying attention, trying their best, but normal people rather than career weight-lifters. The Dutch scientists sometimes did the experiment exactly as we've just described it: "squeeze when the word appears on the screen and stop when it vanishes." But sometimes they also put a word on the screen that relates to the effort of squeezing, words like "exert" or "vigorous." And sometimes they also put words on the screeen that have positive or pleasant "reward" connotations, words like "good" or "pleasant." Mind you, the screen was set up so that there were various randomized words present no matter what was going on -- the visual equivalent of the noise in the bar with the TV I mentioned earlier. But I'm not going to go into all that. The point is, sometimes there were words related to squeezing itself, as an effort, simply present to the subconscious mind of the person doing the squeezing. And sometimes, in addition, there were positive rewarding-type words present as well, again for perusal by the subconscious mind. The only thing the conscious mind registered was the instructional word "squeeze" when it appeared and then disappeared. And here are the results.

The black line shows you what happened when these normal people just normally squeezed the gripper, with normal kinds of thoughts in their conscious and subconscious minds. You see the normal lag time it took them to generate full gripping power, the peak at about 35 Newtons, the slow diminishing of grip strength after the peak, and then the drop after "squeeze" left the screen and they let go. Now look at the blue line and the red line.

The blue line shows you what happened when people were "primed" first -- when they were shown, subliminally, a word relating to grip strength like "exert". Notice, they were not seeing people grabbing things or a movie of a gripping hand with tendons standing up with effort; nor were they being given words in a way they were consciously aware of. No one said, "Listen here, Hans: exert yourself." No. But they might as well have, because that's exactly what their bodies heard. The blue line shows a much faster response to the initial appearance of the word "squeeze" on the screen -- look how quickly the curve rises. The person who had been primed by the word "exert" (for example) was ready to go when "squeeze" showed up, so they went right at it with a fast grip. They squeezed harder, too -- up to 50 Newtons before their grip began to relax. The only difference between these people's efforts and the ones shown by the black line are that they'd been subliminally exposed to one of five effort-related words before "squeeze" showed up on-screen. As a result, they reacted more quickly and with greater strength.

Now look at the red line on the graph. The people whose responses are recorded by this line also saw a subliminal word related to exertion before "squeeze" showed up -- and, in addition, they saw a subliminal word like "good" or "pleasant" that has positive, reward-type connotations. That's all. Both words were subliminal, and both were merely the breath of an idea floating around this whole moment in time. Their response time was as fast as that of the blue-line people who'd been "primed" without the reward-added word, but their grips were much stronger: 70 Newtons of force -- twice the grip strength that was recorded during their "normal" efforts!

So what, you may ask? Well, so this. I mentioned the crowded, noisy bar at the beginning of this musing for a reason: it's a common environment these days. Whether you're waiting for a plane in an airport terminal or putting one of those paper thimbles of cream into a cup of "Continental Breakfast" coffee in a hotel lobby, there's likely a TV playing in the background. People are talking, elevators are dinging, ticket agents are announcing delays on the PA -- and people are shooting each other, making their carpets smell fresher, and accusing their spouses of infidelity in the background at the same time. It's a constant subliminal stimulus -- one might even say the sound track of modern life. What's in it, related to our bodies and the efforts in which we may engage? Do we receive stimuli that make us respond more quickly to things in our environments, with more force?

"Priming" a pump means running a small amount of already-on-hand water through it to create a path by which underground water can come up faster and more easily. If you want someone to squeeze a gripper, you can prime their gripping muscles by running certain words past their subconscious mind; it makes the response you want faster and stronger. That's why the scientists who did the Dutch study referred to the people who'd been given subliminal cues as "primed". But emotions, as well as physiological processes such as heart rate and muscle contraction, are controlled at a base level by our neuro-endocrine system of nerves and hormones, too. The research paper was about "Preparing and Motivating Behavior Outside of Awareness", where the "behavior" was squeezing a gripper device. It doesn't take much imagination to see how their results might be applied to a much wider range of human behaviors, including their attendant (physically connected-through-the-limbic-system) emotions.

What does it mean about the ways we react in our "normal" lives, given that we are being subliminally primed for all sorts of physiological and emotional responses, pretty much constantly? Do we tend to see someone sitting down next to us in the airplane as a hot date or a terrorist based on what happened to be playing on the lounge television before we boarded? Do we respond more strongly and insistently, either way, if that television program linked the landing of a hot date or apprehension of a terrorist with "good" or "pleasant" things?

Advertisers and the psychologists who work Hollywood audiences assume so, though with presumably less data. (That's why the Dutch study got published in Science, a prestigious journal with a lot of competition for space, is that the data are so solid.) But advertisers and Hollywood types probably think what a lot of us think: that when we're primed, we somehow know it. We find ourselves humming the commercial jingle in the cereal aisle, so at least it's not like we're being brain-washed. We know when we're responding to stimuli that pair up "good" with "Corn Flakes" or "Cheerios". Right? Wrong.

One of the most distressing parts of the Dutch study is the fact that "Participants were also asked to indicate how hard they tried to squeeze into the hand-grip. Crucially, no significant differences emerged. This finding indicates that the subliminal priming of the concept of exertion did not lead to an increase in conscious awareness of exerting effort, thus supporting the claim that differences in behavior are due to largely nonconscious mental processes." In other words, the testees thought they squeezed the gripper the same way, equally hard, every time. They not only didn't know they'd been primed differently at different times, they didn't know they'd responded any differently at different times. Unless someone measured their grip and told them the reading, they would not and did not know it was stronger on the occasions when it was. They figured it was all of it -- all of it -- "normal."

I leave it to you, what you want to do with this information. For myself, I think I'll go sit in the main dining room the next time, if the TV is on in the bar.

Dawn Adrian Adams, Ph.D.